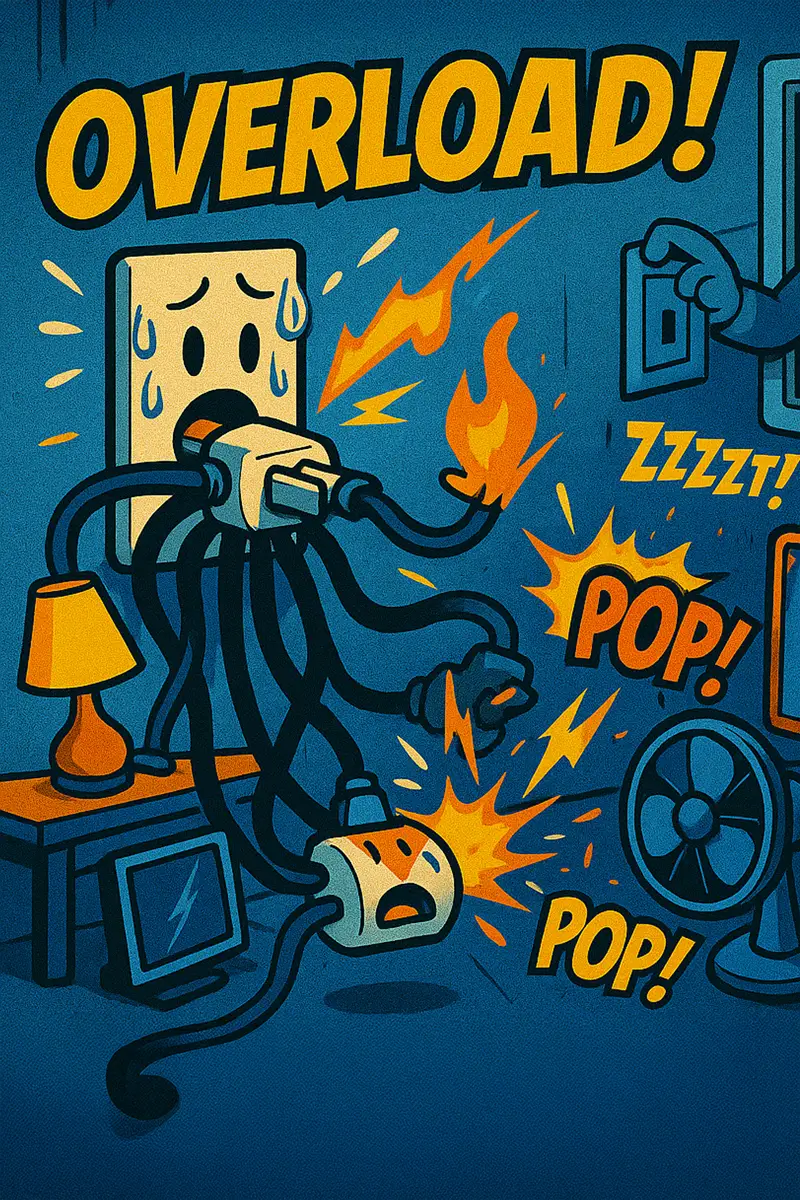

An overloaded circuit occurs when the electrical load (the total demand of all devices) on a single circuit exceeds what that circuit is designed to handle. In practical terms, it’s plugging in or running too many appliances at once on one circuit. Symptoms of an overload include the circuit breaker tripping (the most obvious sign), lights dimming when a large appliance turns on, or outlets and plugs feeling warm. You might notice that using the microwave and toaster together in the same kitchen outlet causes a shut-off – that’s a classic overload scenario. Sometimes, if a breaker is oversized or faulty, you won’t get an immediate trip, but the wiring can get hot – so flickering lights or a mild burning smell could also hint at an overload condition.

Overloaded circuits are exceedingly common in the DMV for a simple reason: many homes (especially older ones) weren’t wired for the sheer volume of gadgets and appliances we use today. Think about a 1950s Arlington house – it likely had one general circuit for all the receptacles in the living and dining room. Now fast forward to 2025: that same space might have a big-screen TV, cable box, surround sound, a couple of lamps, a phone charger, and maybe an AC window unit on a hot day. Boom – overload city. Historic homes in DC and Annapolis often have fewer circuits, meaning multiple rooms share the load. High energy demand in modern living (hello, espresso machines and gaming computers) quickly fills up those amps. The geography plays a role too – space can be at a premium, so people use power strips rather than running new circuits. We also see seasonal overloads: in winter, plugging multiple space heaters into one room’s outlets (older heating-challenged townhouses, we’re looking at you) or in summer everyone running dehumidifiers and portable ACs. Additionally, the rise of home offices and home theaters in suburbs like Fairfax means circuits originally meant for a couple of lights are now powering multiple computers or a mini-fridge and treadmill in the garage. Simply put, our usage has outgrown many home’s original wiring designs, leading to overload scenarios on the regular.

When a circuit is overloaded, it’s like a highway carrying too many trucks – something’s gotta give. Best case, the circuit breaker trips and cuts power, relieving the overload. But if for some reason the breaker doesn’t trip (say it’s old or improperly sized), the wires themselves can overheat. Hot wires can melt insulation, leading to short circuits or arcing, which dramatically increases fire risk. Even with a functioning breaker, repeated overload trips can wear it out, possibly delaying its response time (a worn breaker might trip later than it should, allowing more heat buildup). Another risk is damage to appliances. Low voltage conditions (which happen just before a breaker trips) can harm motors and electronics – like your fridge or computer doesn’t appreciate getting undervoltage because the circuit is sagging under load. And of course, there’s the immediate inconvenience/safety issue: overloaded circuits often go out at the worst times (mid-dinner prep, or when a space heater is preventing pipes from freezing). That sudden loss of power can be more than a hassle; in some cases, it might leave you in the dark or without heat on a dangerous cold night. Lastly, constantly resetting tripped breakers due to overloads means you might become desensitized to breaker trips – and miss other warning signs of trouble. So, the risk spectrum ranges from annoying disruptions to significant fire hazards if not addressed.

If you’ve mapped out that “every time I do X, the breaker trips,” and X is something reasonable (like running the vacuum and the heater simultaneously), it’s a sign that your circuit is consistently overloaded. You should call an electrician to discuss better distribution of power. Specifically, call a pro when: a particular breaker trips repeatedly even after moving some loads around; you find yourself using a lot of extension cords or power strips as a workaround (an indicator you need more circuits/outlets); or you notice any buzzing at the panel or scorched outlets which may indicate the overload is causing physical damage. A licensed electrician can evaluate your home’s circuit layout vs your usage. Often the solution might be adding a new circuit or two to heavy-use areas (kitchens, home offices, media rooms) so that high-draw appliances are separated. They might also redistribute some loads across existing circuits if possible, or upgrade a circuit’s wiring and breaker (for example, going from 15 amp to 20 amp in a workshop, if the wiring gauge allows). Importantly, they’ll check that the breaker size matches the wire size – sometimes we find an “overfused” circuit (e.g., a 20A breaker on 14-gauge wire) which is a hazard for overload because the breaker won’t trip early enough. The electrician could also recommend energy-efficient upgrades (like LED lights or modern appliances) that draw less power, easing the load. Ultimately, an electrician’s job is to ensure your system can handle your lifestyle safely. Think of it as a capacity upgrade for your home’s electrical “brain” – giving it the ability to multi-task without breaking a sweat (or a breaker).

Powering your home shouldn’t be like a game of Jenga, where one more device brings the whole tower down. If you’re constantly doing the “unplug dance” (unplugging one thing to run another), it’s time to level up your circuitry. In true heroic fashion, Dr. Electric can rewire the battlefield, dividing and conquering those heavy loads so every device gets the energy it needs. It’s all about balance – even electricity needs a well-planned strategy. Don’t let an overloaded circuit be the villain that repeatedly knocks out your lights; call in the heroes to give your electrical system the strength to carry the load.

Dr. Electric offers a range of services to enhance safety, reliability, and performance. Get in touch or check out our List of Common Electrical Requests.

You can also text our support team at 833-337-3532 or email: info@drelectric.com